Between mid-September and mid-November 2020, the research team of the Health Poverty Observatory of the Banco Farmaceutico Foundation carried out (under the scientific direction of the writer) a survey on a sample of 221 organisations, representative of the 892 charities most organised in terms of responding to the health needs of the poor. This research was important for understanding the impact of the pandemic on charitable organisations and, through them, on individuals in health poverty conditions .

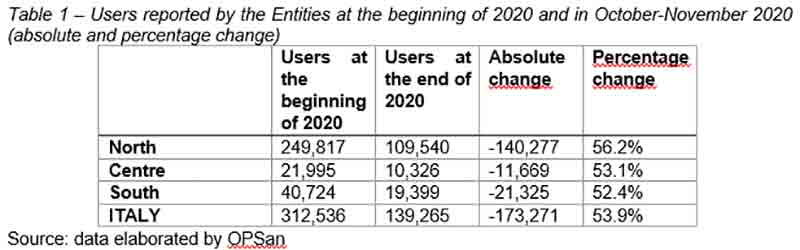

Thus, it was possible to estimate the quantitative and qualitative consistency of the 'Covid-19 effect', which was both predictable and unexpected. Table 1 summarises this paradoxical double effect. At the beginning of 2020, the organisations analysed (equal to 48% of the total organisations supported by the Banco Farmaceutico Foundation) provided aid to 312,536 people (equal to 72% of all the individuals assisted by the Foundation in Italy). This is therefore a significant sample, which not only represents a large part of the total number of users, but also the most structured component (and therefore presumably the most solid and well-equipped in terms of technical and human resources available) of the organizations in the BF network.

Precisely for these reasons, the data recorded between October and November appears particularly dramatic, when the number of aid beneficiaries fell to 139,265, a decrease of 53.9% compared to the beginning of 2020. This is a significant decrease, which is moreover equally distributed among the macro-areas of the country, with a slight sharpness in the northern regions (where historically the largest number of non-profit organisations is also present).

The drastic decrease in the number of people assisted seems to have changed the profile of the poor who turn to the proximity services managed by charitable organisations. If at the beginning of the year the distribution of the assisted people was moderately unbalanced in favour of foreigners (53.2%) compared to Italians (46.8%), the data recorded by the research show a deep transformation: foreigners have increased to 65.2% of the total and, consequently, Italians have decreased to 34.8%.

Therefore, why is it that while the number of poor people increased, the number of people receiving care decreased so significantly? There are two possible explanations: a decrease in demand (withdrawal from care), a decrease in supply (reduction in activities on the part of the institutions).

Our research does not support the first hypothesis since it focuses mainly on the institutions and therefore on the supply of services. However, we know from numerous sources that in general there has been a reduction in the demand for health services in recent months, mainly due to the fear of contracting the virus within the various hospital structures. It is possible to hypothesise a similar dynamic with regard to health poverty: above all the Italian population in conditions of poverty has given up using the specialised health services offered by charitable organisations.

Besides this hypothesis, our research gives us, instead, strong evidence about the decrease in the response capacity of charitable and proximity organisations. Only 53.5% of the charitable organisations could continue their activities in a regular way, while 40.6% suffered from strong limitations (including the closure in some periods) and the remaining 5.9% had to close their doors in a permanent way.

The decrease in the number of people assisted is therefore also (and perhaps above all) due to the impossibility of finding the non-profit organisation one was used to.

At the same time, it can also be observed that the size of the organisation (which is obviously a proxy for more complex organisational forms and the presence not only of volunteers but also of employees) has a significant influence on the number of users: almost 62% of the large organisations reported a reduction of more than 40% in the number of people assisted, in addition to 13.7% who reported a reduction between 5 and 39%. On the other hand, less than half (41.1%) of the small organisations reported a reduction in users: a sign, perhaps, of greater 'resilience' on the part of the smaller organisations, which are better able to absorb even significant social and/or health shocks.

The health spending capacity of the poor: an Italy divided into nine

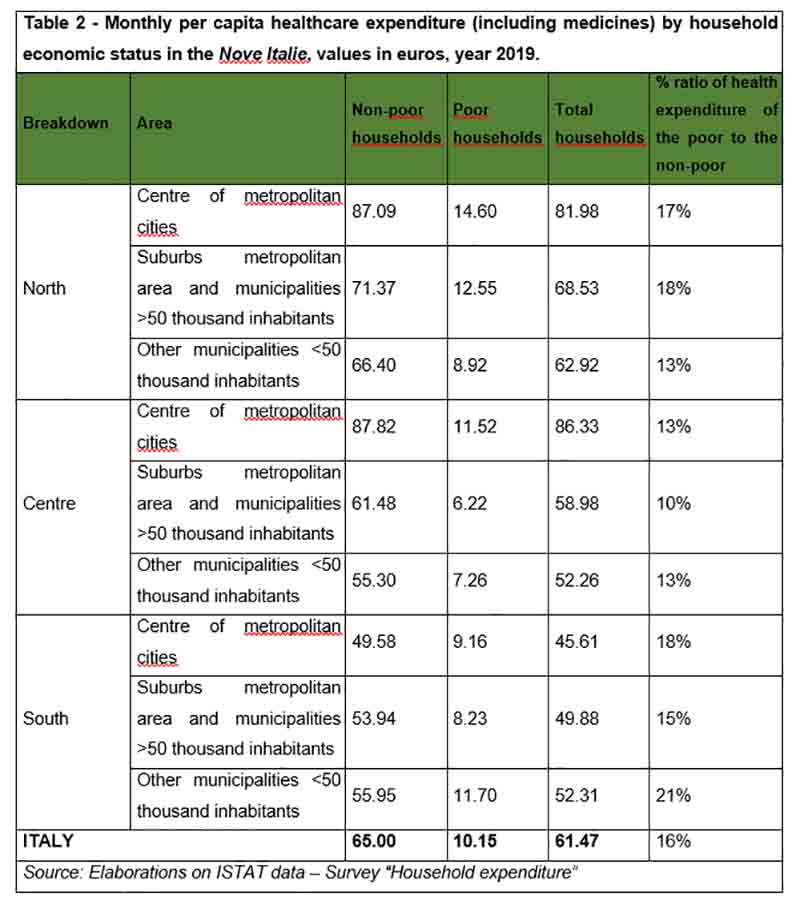

These data, contained in the most recent Report published by the Observatory, confirm the existence of a problem of 'health poverty', which worsened during the pandemic, but which pre-existed it. The elaborations on ISTAT data contained in the Report are dramatic from this point of view. Individuals in absolute poverty (i.e. those who cannot buy the essentials for a dignified life) can afford a per capita health expenditure equivalent to 1/6 of that borne by people who are not poor (€ 10.15 vs. € 65). A more detailed reading of this average data reveals the existence of nine Italian territories of poverty, with greater inequalities in the municipalities bordering metropolitan centres and in municipalities with more than 50,000 residents in Central Italy (€ 6.22 vs. € 61.48) and smaller differences in the small municipalities of Southern Italy (€ 11.70 vs. € 56). The territorial comparison among the poor shows a significant variation in their monthly health expenditure, which reaches its lowest value (€ 6.22) in the intermediate municipalities (with more than 50,000 residents) of Central Italy and its highest value (€ 16.60) in the metropolitan municipalities of Northern Italy (Table 2).

These comparisons document a strongly unequal reality from the point of view of the basket of health goods and services that can be purchased and, consequently, of the capacity to protect one's own health, in terms of both prevention and treatment. This has dramatic repercussions with regard to the issue of the 'renunciation of treatment': more than twice as many poor families as non-poor ones (31% vs. 14.7%) declare that they have renounced regular medical check-ups and preventive examinations, with a peak of 63% for poor families in the metropolitan areas of Southern Italy, where 38% of non-poor families have renounced treatment. The consequences of not having these check-ups will weigh for a long time in terms of morbidity and mortality and will produce further inequalities in the population. This is an emergency that we as a community must tackle immediately, and with respect to which the Catholic University has made a proposal to develop a specific intervention within the Recovery Plan, in collaboration with the most important Italian third sector companies.