Since the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and the related containment policies have modified the environment in which organized crime groups (OCGs) operate. COVID-19 generated pressure for rapid and effective governance to contain the pandemic and the resulting economic recession. Consequently, we focused our research on two distinctive features of OCGs: (a) their capacity to present themselves as providers of governance and (b) their capacity to infiltrate the legal economy.

The identification of real-life cases was based on a systematic content analysis of international, national and local media articles and institutional reports published during the first eight months after the outbreak of the pandemic (January to August 2020). News articles were retrieved from digital repositories and news aggregators, while institutional reports were obtained from international and national authorities as well as civil society organizations. The dataset of collected cases included 29 unique cases retrieved from 21 sources worldwide. Languages considered include English (14), Spanish (9), Italian (3) and Portuguese (3).

Illegal governance

The means with which OCGs tried to exert and expand their governance role can be classified into two main categories. The first one relates to the groups that provided sustenance and facilitated access to resources that people need. For instance, food and primary goods were distributed by Cosa Nostra and Camorra affiliates in the Italian cities of Palermo and Naples. Members of rival gangs in South Africa’s capital Cape Town made truce and agreed to distribute basic goods for people in need. Similarly, members of several drug trafficking organizations in Mexico supplied bundles containing food and sanitizers to the states and cities under their influence. Sanitary equipment was also distributed by gang members operating in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and by yakuza members in Japan.

A second category of governance activities includes the imposition and the enforcement of social distancing measures and the performance of other policing activities. For example, several Brazilian gangs prohibited tourists from entering the favelas in Rio de Janeiro while also imposing curfews and the closure of shops. Likewise, gangs in Venezuela and El Salvador enforced government-mandated lockdowns and restricted public gatherings in the territories under their control.

We also found cases of other criminal insurgency non-state entities that did engage in governance activities, such as the Fighters from the dissident 29th Front of the ex-FARC in Colombia, the Taliban in Afghanistan and the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in Syria, who have all engaged in policing activities, enforcing quarantine measures and restricting public gatherings.

Infiltration of the legal economy

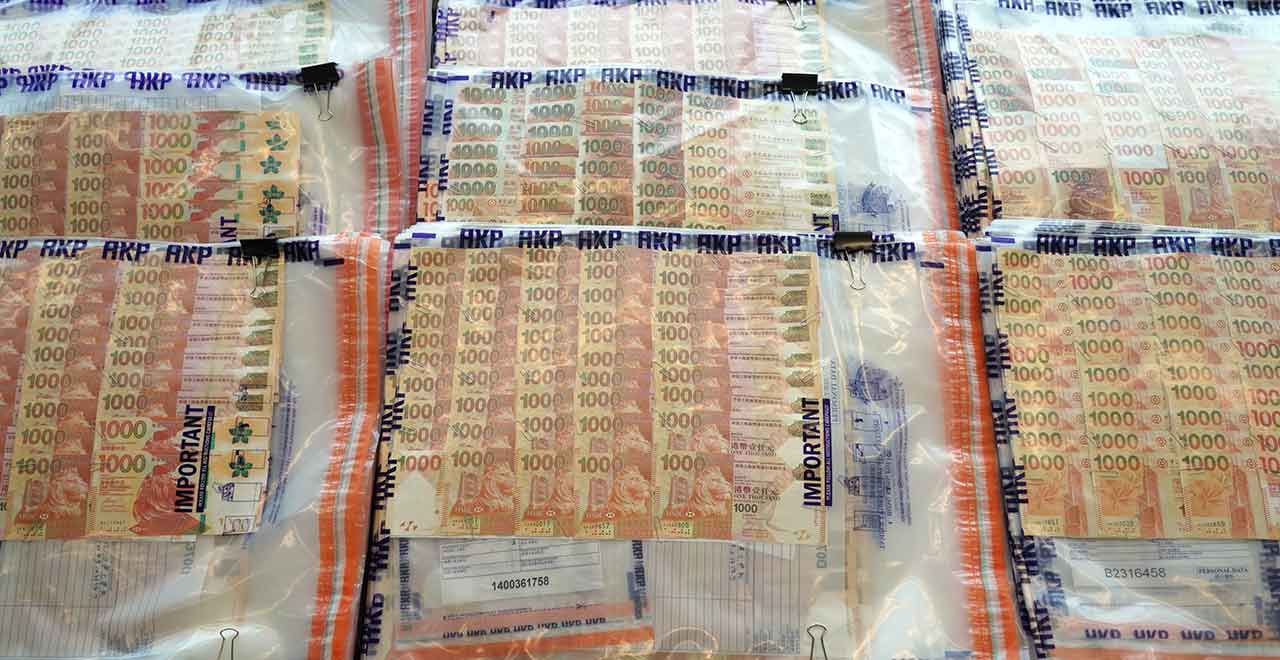

The economic sector identified as being most vulnerable to and exploited by criminal infiltration was the wholesale trade in medical and pharmaceutical products. Operation Pangea XIII, coordinated by Interpol, ended up with the massive seizure of many dangerous pharmaceuticals and medical products. It involved police, customs and health regulatory authorities from 90 countries and resulted in 121 arrests worldwide. Other cases of large-scale distribution of counterfeit and defective pharmaceutical products were reported by law enforcement agencies in several European countries, including Romania, the United Kingdom, Belgium and Lithuania.

We also identified cases of misuse of public funds intended to support medical needs and to stimulate the economic system. These included a case of corruption in the procurement process whereby funds intended for protective equipment were misappropriated by a well-known OC member in Slovenia. In addition, we found a case of a massive fraud scheme coupled with money laundering concerning the supply of 10 million face masks worth €15 million in which German health authorities were scammed by criminal groups located in Spain, Ireland and the Netherlands. Finally, the analysis highlighted a case of embezzlement of Italian economic relief packages valued at €45,000 that were awarded to a ‘ndrangheta member through a complex scheme of tax fraud, false invoices and fake names.

Italy and risk of criminal infiltration

A recent study conducted by Transcrime (the joint research centre on transnational crime of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore) on more than 43,000 Italian companies that reported the change of at least one beneficial owner (BO) during the first phase of the pandemic (April to September 2020), highlighted two main potential risks of infiltration through the use of corporate vehicles.

First, it was found that 1.3% of these firms had BOs or shareholders registered in jurisdictions included on greylists and blacklists issued by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the European Union (EU). This value was 5 times higher than the average of Italian companies. Second, 1.4% of these companies were controlled by a trust or an opaque legal arrangement that impeded the identification of any BOs. This value was 10 times higher than the average of Italian companies.

We found that different governance-type criminal groups proposed themselves as institutions able to mitigate the burdens imposed by the pandemic by providing support to people in need and enforcing social-distancing measures. Cases of misappropriation of public funds and organized crime infiltration of the legal economy seem less common, at least in the first phase of the pandemic. The wholesale distribution of pharmaceuticals and medicines was the most targeted sector.