The persistence of the coronavirus–caused respiratory disease (COVID-19) and the related restrictions to mobility and social interactions are forcing a significant portion of students and workers to reorganize their daily activities to accommodate the needs of distance learning and agile work (smart working).

A common experience between Individuals experiencing distance learning and smart working is the feeling of tiredness, anxiety, or worry resulting from the overuse of virtual videoconferencing platforms - so called Zoom fatigue. With this term psychologists describe a feeling of fatigue and discomfort linked to the numerous videoconferencing sessions that represent the main communicative tool used during distance learning and smart working.

Why are we experiencing this Zoom fatigue, and what is its impact on the processes of learning and working? The most common explanations are that technology often does not work optimally and videoconferencing reduces nonverbal cues. Additionally, though not perceived consciously, the slight delays in videoconferencing force our brains to work harder to overcome and restore synchrony to our communications.

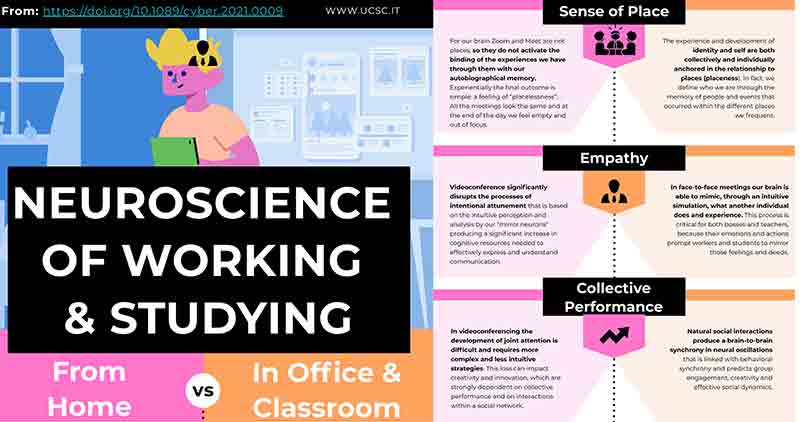

However, as discussed by the recent paper “Surviving COVID-19: The Neuroscience of Smart Working and Distance Learning” (https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0009 - Free Access) written by Giuseppe Riva, Brenda K. Wiederhold, and Fabrizia Mantovani, the scenario is more complex than it may appear at first glance.

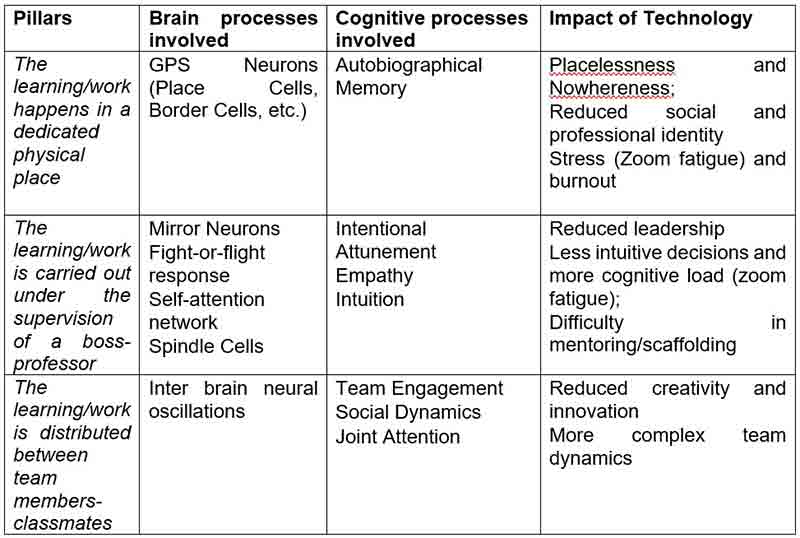

The authors used the recent reflections and neuroscience research findings to explore how distance learning and smart working impact the following three pillars that reflect the organization of our brain and are at the core of school and office experiences:

a. Sense of Place (Placeness): the learning/work happens in a dedicated physical place;

b. Leadership, Empathy, Intuition, Mentoring/Scaffolding: the learning/work is carried out under the supervision of a boss/professor;

c. Group Identification, Collective Performance and Creativity: the learning/work is distributed between team members/classmates.

As explained by Prof. Giuseppe Riva, full Professor of Communication Psychology at the Catholic University of Milan, Italy: «Recent neuroscience research suggests that videoconferencing affects the functioning of GPS neurons - the neurons that code our navigation behavior - mirror neurons, self-attention networks, spindle cells, and interbrain neural oscillations. These modifications, discussed in the paper, produce a significant impact on many identity and cognitive processes, including social and professional identity, leadership, intuition, mentoring, and creativity».

First, the use of videoconferencing can generate a sense of placelessness that has a direct impact on our episodic memory, our personal and professional identity, and increases the risk of burnout. More, the lack of intentional attunement and the difficulty in taking intuitive decisions has also a strong impact on leadership and on all the mentoring/scaffolding activities. Finally, the impossibility of using eye contact and the exchange of glances, the main tools used to generate joint attention, reduces group engagement, collective performance and creativity.

A summary of the results of the paper are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. The impact of smart working and distance learning on different brain and cognitive processes

Prof. Brenda K. Wiederhold, author of the paper and Editor of the Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking journal concludes that; «just moving typical office and learning processes inside a videoconferencing platform, as happened in many contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic, can in the long term erode corporate cultures and school communities. In this view, an effective use of technology requires us to reimagine how work and teaching are done virtually, in creative and bold new ways».

As suggested in the paper, a possible strategy to drive these efforts is to use technology to generate and support “communities of practice”, groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting digitally on an ongoing basis. For example, the groups of adolescents meeting daily in social videogames like Fortnite or Among Us, represent a clear example that it is possible to develop successful communities even without a physical place in which to gather together.